Originally published in Frieze, October 2017.

The past cannot necessarily be reasoned with, nor simply erased. In Kyiv, a city of turbulent history, this is not simply a conceptual question but a pressing political problem. Recently I visited the Visual Culture Research Center (VCRC), a collective of artists, activists, curators and researchers based in central Kyiv. I sat in their second-floor office and watched CCTV footage on a mobile phone. On 7 February 2017, 15 men entered the gallery with their faces concealed. They assaulted the guard, destroyed the exhibition, and left. They were never identified. You can watch the video on YouTube. For me – a coward – to watch such violence, in the very space where it took place, was an unsettling experience. It wasn’t the first time either: some of the team were attacked in the street in 2014, from when director Vasyl Cherepanyn is yet to fully recover.

Why is this happening? In February 2013, the Maidan revolution forced the hugely corrupt pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych to flee the country. The following month, Putin annexed Crimea. The new government of Petro Poroshenko – also considered corrupt – has embarked upon a policy of ‘decommunisation’ as part of a social and political pivot away from Russia, towards Europe. In addition to removing monuments and changing place names, new laws have branded the Soviet Union ‘criminal’. Ukraine’s communist parties are banned from elections. As Soviet-era architecture is swept aside by developers, many believe that the policy has also fuelled tolerance of violence. ‘Ukrainian right-wing radicals feel more confident than ever to attack and destroy whatever they do not like,’ says VCRC’s Anna Tsyba.

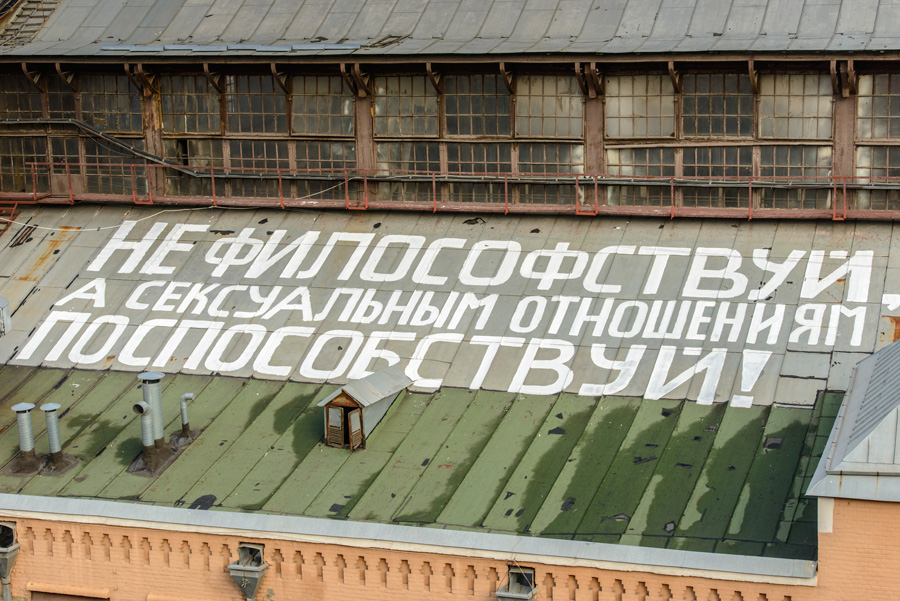

In response, a counter-current of artists, activists, academics and researchers is attempting to rethink Ukraine’s past in more productive fashion. In 2015 VCRC along with curators Hedwig Saxenhuber and Georg Schöllhammer, helped to organize the ‘School of Kyiv’, a new biennial with an international scope, which saw exhibitions and event taking place in multiple locations across the city. Politically astute artists such as Sasha Kurmaz see the city as site of complex tensions between competing interests. By Holosiivska metro, artists occupied a vast, dilapidated former film school ahead of September’s Gogolfest festival of theatre and performance. Nightclub Closer hosts art exhibitions in a ribbon factory built in 1896 – when Kyiv was part of the Russian empire.

Continue reading on frieze.com