Originally published in Frieze, March 2017.

‘Paris is no longer Paris.’ That’s what Jim said. And Jim is ‘a very, very substantial guy’ according to Donald Trump, citing ‘his friend’ in a recent speech to the Conservative Political Action Conference in Maryland. Both French President François Hollande and Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo hit back: inviting Trump to Disneyland Paris and reminding him he might have issues to worry about closer to home, such as the open sale of guns in the US and its own homicide levels. Touché. But could it be that Jim has a point, even if not exactly in the way he, or Trump, conceives?

Paris has changed. Since the terrorist attacks of 2015, France remains in a state of emergency – one that has been extended five times, the latest period until 15 July, after the presidential elections. During this time, more than 4,000 homes have been searched without judicial authorization. There are security checks at the entrances to all major museums and department stores. The prominent presence of armed police at Paris’s famous landmarks and the plan to build a bullet-proof wall around the Eiffel Tower demonstrate the state’s desire to protect the city from any repeat of what Hollande described as ‘an act of war’.

But terrorism is not a pitched battle between clearly defined nation states, and France’s security forces are at risk of treating its own people as enemies. Certain people, that is, more than others: the horrific rape by police officers of a young black man named Théo, and the subsequent pattern of protest and crackdown, have emphasized the deep racial divisions within French society. During a recent walk around the independent galleries of Belleville, I watched as a squadron of paratroopers progressed in formation up Rue Jean-Pierre Timbaud (named, incidentally, after a trade union leader and Resistance fighter executed by the German army in 1941). The presence of the army in residential areas of Paris prompts new questions: who is being protected? And from what?

Conflict between citizens and police is not new here. At Maison Rouge, a private foundation established by supermarket heir Antoine de Galbert, the patchily fascinating exhibition ‘L’Esprit Français’ charts the history of French counter-cultural currents from the aftermath of 1968 to the end of the 1980s. Art, ephemera, and archival materials show how a dominant culture asserts itself through the demonization of an absent or voiceless Other: ‘Les habitants d’Alger sont des pirates,’ reads a French handwriting exercise from 1970: ‘The inhabitants of Algiers are pirates.’ At the same time, divisions along lines of race and class are both accentuated and repressed: on the April 1973 cover of Charlie Hebdo row upon row of faceless police are turned towards distant tenement blocks, presumably to prevent the residents of les banlieues from ever reaching us viewers.

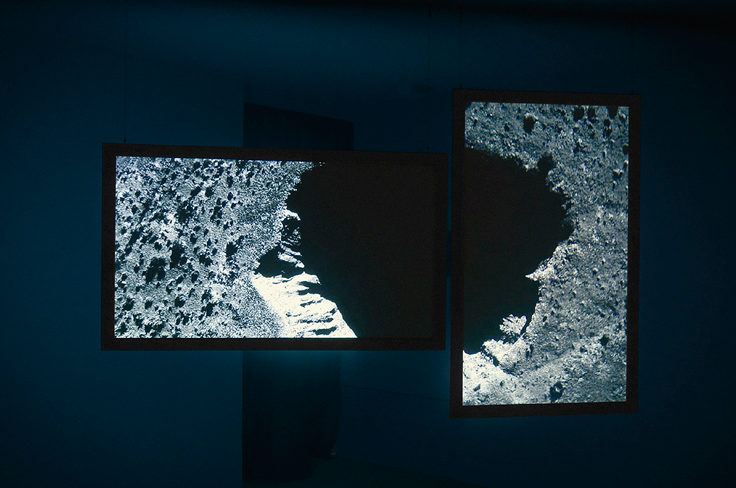

If politics today obsesses over the policing of borders, art in France is enacting multiple crossings through a renewed interest in language and translation, testimony and bearing witness. At Kadist in Montmartre, Turkish artist Barış Doğrusöz tells of the literal undermining of walls in an entrancing two-screen video work about the ancient multicultural fortified Syrian city Dura-Europos, recently demolished by Daesh. At Belleville-based Galerie Crèvecoeur, Xavier Antin refers to coded communication between the ‘square men’ – members of the International Typographical Union, a trade union for the printing trade, in 19th century America. There are moments of beauty too: at Galerie Jocelyn Wolff is the work of William Engelen, who translates music into delicate, repetitive drawings and exquisite sculptural pieces.

In today’s political context old works can take on new meanings. At the Louvre’s exhibition of French Baroque painter Valentin de Boulogne, knives balance right on the edge of tables. I can’t help but think of Katinka Bock’s crumpled ceramics perched precariously atop upended wooden beams (also at Jocelyn Wolff). In The Spectator, historian Robert Tombs asks whether France is ‘on the brink’ of revolution. Amnesty International has declared that human rights in the country have reached a ‘tipping point’. Currently Marine Le Pen leads the presidential polls. Unlike Trump or Brexit, Le Pen appeals to the young. At Frac Ile-de-France’s Le Plateau space, in the group show ‘Strange Days’ something small has already fallen: a yoghurt pot from a low-level pedestal, part of Ian Kiaer’s 2009 installation Offset / black tulip (black). Such signs of uncertainty feel potent now.

Boulogne’s richly evocative depictions of biblical scenes seem to me to flex under the yoke of a triple politicization: the time of the subject matter (the occupying Roman regime); of the painting (under the might of the Borgheses); and now of the viewing in the securitized museum. In The Crowning with Thorns (c. 1613–14), Jesus’ naked flesh emphasizes his vulnerability and courage before the armed and armoured Romans. Then, in Christ and the Adulteress (c.1620s), we see Jesus defending an accused woman against assembled soldiers. Light shines on his bare forearm as it does upon her breast. Outside the frame he is writing in the sand (in Aramaic? in Latin?): ‘Let him who is without sin cast the first stone at her.’ These soldiers may be handsome and human, unlike the mechanized legions of the Charlie Hebdo cover, but they are still powerful, dangerous, and unpredictable. One has his armoured back to us: his right arm cuts the composition in two; his left hand is poised at his hilt. The Bible tells us the story ends well, but history rarely keeps its promises.