Originally published on Spoonfed, October 2011.

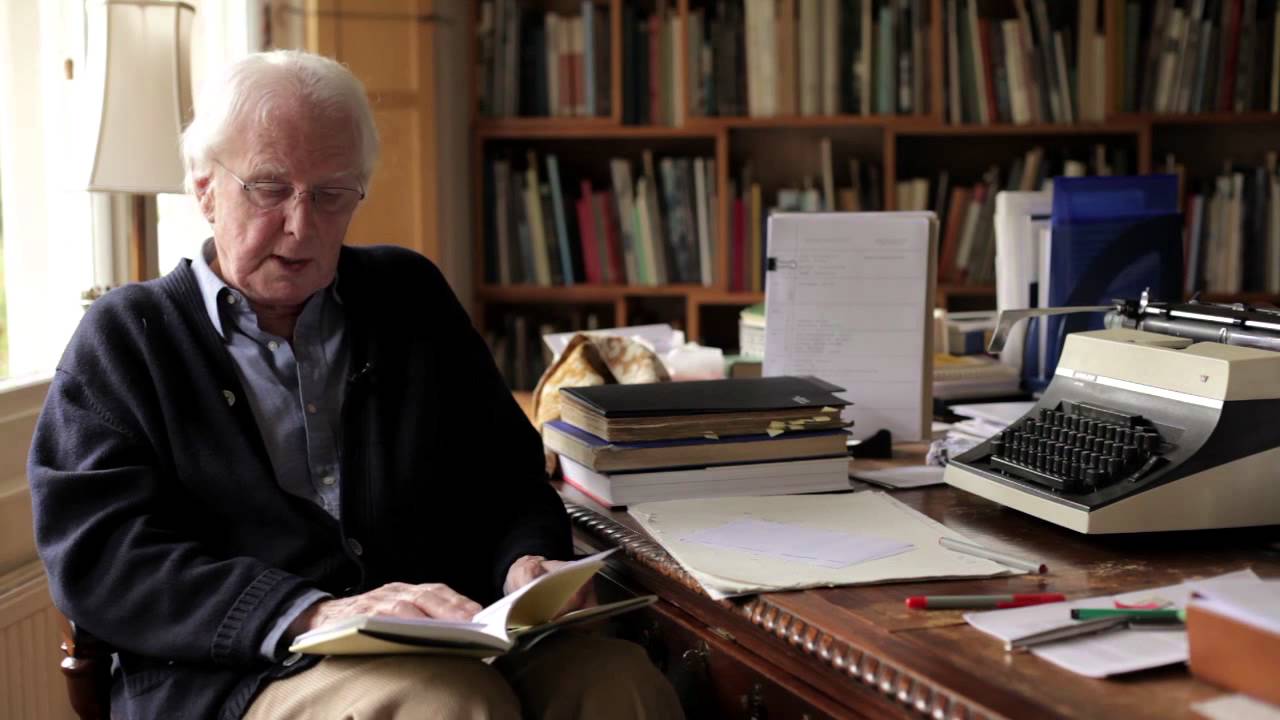

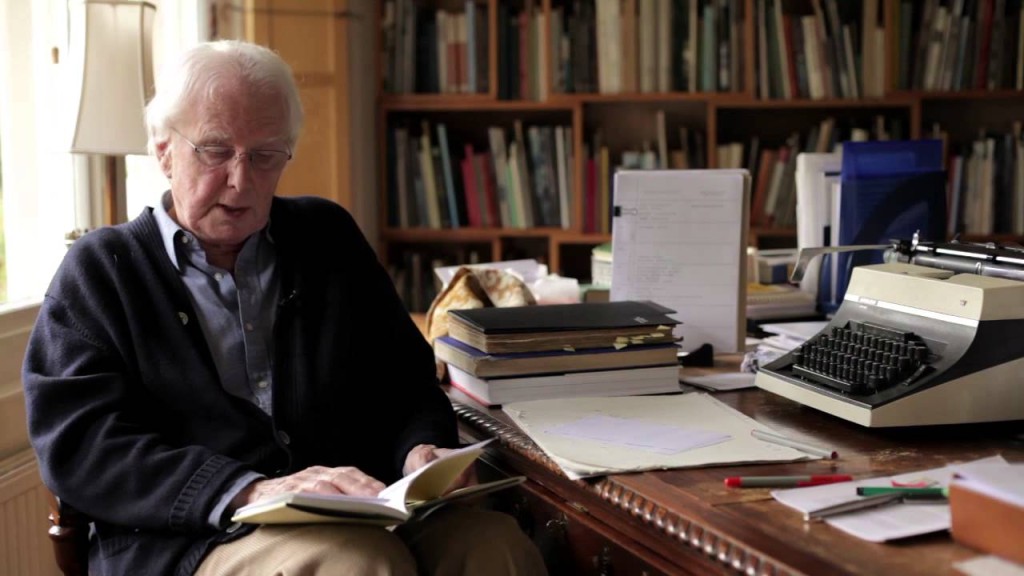

It’s a good half-hour or so since I arrived at the Wimbledon home of legendary art critic Brian Sewell. Already we’ve discussed the V&A’s Postmodernism exhibition, the new Grayson Perry-curated show at the British Museum, and the editor of the Evening Standard (none of which Brian is very keen on) as well as Brian’s pet dogs, Pope Clement V, and the tale of Abraham the Jew in Boccaccio’s Decameron (about which he is much more enthusiastic). Of course, when I say “we’ve discussed”, I really mean that Brian has held forth, with that combination of mischief and brutal honesty that has made him both so loved and so reviled. All the while I sit mainly in silence and in awe, slightly amazed that I’ve been allowed into his home, and hoping not to say anything too stupid.

All of a sudden he turns to me. “So. Why are you here?” It’s not so much rude, as simply direct, and in that familiar, haughty voice, with all its painstakingly precise enunciation (Whay are hyou hyuh?). I have to admit I’m rather thrown.

So, why am I here? Well, because at the age of 80, Britain’s most forthright art critic is turning his hand to curation. Sewell, the Evening Standard’s art critic since 1984, is curating a solo show for contemporary artist Richard Harrison that opens to the public this October in the unusual surroundings of Jamb, an antiques dealership near to Sloane Square.

However, after innumerable pannings of curators (those at the Tate in particular), Sewell is keen to avoid the idea of himself as curator: “’Curate’… is rather a strong word for it,” he says. “I mean I will help to hang what is there. A retrospective is really the only kind of exhibition to which you can apply the curatorial word, because you have all the work to choose from – or if you’re dealing with more than one painter and looking to find links and oppositions and so on. This is really just a case of choosing some paintings.”

It’s a little more than that though: while I’m here Richard and Brian go through several of the potential paintings together, using Richard’s iPad. This leads to the occasional amusing outburst (“Oh fuck. Oh bugger. Why’s it done that?”) but also provides a fascinating insight both into Brian’s admiration for Richard’s work, and Richard’s appreciation of Brian’s extremely honest observations.

“Sometimes you dash at the human figure without considering it,” he tells Richard at one point, “and you’re not very good at male figures. I think you need a model. You need to understand how seductive a male figure can be.” Then, a little later, “this horse looks more like an ass – a winged mule. Give it a bit of dignity!”

Not many artists I know would take the kind of criticism that Sewell dishes out in his own inimitable style, and he knows it: “He’s very good isn’t he! Any other painter would have boxed my ears by now.”

The two clearly share a great friendship, forged out of a shared view on what art should be and do. “I encountered Richard as a mature pupil at Chelsea 25 years ago,” Brian tells me, “and was profoundly impressed. I have done what I can ever since to…nudge things along.” In 2010 Sewell wrote a book about Harrison, entitled Nothing Wasted – the same title as the forthcoming exhibition. Out of the accompanying solo show at Albemarle Gallery, Harrison was given another solo show, at Chenshia Museum in China, making him the first British artist to be given such an exhibition at a private museum in China – a major accolade.

“I have a certain notoriety,” Sewell continues with not a trace of satisfaction, “and I think that in itself will attract some small attention [to the exhibition] but I hope it doesn’t do too much damage. Because I’m pretty well certain that Victoria Miro, for example, will not set foot in something that I’ve had anything to do with.”

What’s he done to upset Victoria Miro so much, Richard and I both wonder. It seems it all stemmed from a 1989 piece in Apollo magazine in which Sewell criticised artist Ian Hamilton Finlay. Shortly afterwards apparently the artist’s heavies then appeared from Scotland, trashed the magazine’s offices, and then turned up at Sewell’s home in Kensington. Fortunately, “when all the banging began and the bell ringing and the shouting and so on” Sewell hid at the top of the house until they went away. Then in Sean O’Hagan’s 2010 interview with Miro in the Observer, she claimed Sewell had been successfully sued by Finlay. Sewell wrote a letter to Miro that “I am informed caused her considerable annoyance.” His final words on the matter: “I’ve never been sued by anybody, and I’ve certainly never lost an argument.”

But Miro and Finlay are not the only ones to suffer at the hands of Sewell’s pithily phrased disdain. He’s particularly severe on the Stuckists (“contemptible”); Lawrence Gowing (“monstrous”); a certain Mayfair gallerist (“Have you seen his three latest catalogues? They are too awful for words.”); and the Courtauld’s current syllabus, in particular a module entitled ‘Getting to grips with Rembrandt’ – “just a silly, simplified way of dealing with something that is really profoundly serious and hugely influential”.

We cover a whole range of other topics besides contemporary art, as Sewell zips from one example to another in order to illustrate his occasionally controversial opinions. He’s very quotable too: “Incuriosity is the death of scholarship” is one of my favourites, as is his response to the suggestion from Richard that his mother has returned to haunt him: “Oh my mother has been haunting me for the last twelve years. It’s what mothers do.” – the ‘doooooo’ elongated right up to the point of parody.

He talks passionately about the importance of Christianity as the founding ideology behind Western culture: “it’s the root of our literature, our art, our music, and particularly our law”. And he laments its departure from schools: “Educationists are shit-scared of being accused of trying to convert Muslims and Hindus and whatnot.” And this is part of the reason why he’s such a fan of Harrison’s work – because his paintings are imbued with the rich symbolism of these ancient cultures.

The two of them are even talking about establishing a movement (tentatively entitled New Victorians) to advocate a return to, as Sewell puts it, “a new high Victorianism, where painters are actually looking at our cultural roots, which are classical and Christian.” Its aims? “It would be wonderful if we could actually encourage more people to attempt to do heroic paintings – heroic in scale, which is what Richard’s are – as well as heroic in subject.”

This is typical of Sewell – outspoken, not afraid to say what he thinks, and prepared to take a clear stand. This is why he’s so respected by fellow journalists (Critic of the Year 1988, Arts Journalist of the Year 1994, winner of the George Orwell Prize in 2003) but so loathed by the contemporary art world, which is largely used to critics acting merely as cheerleaders. Back in 1994 a host of London’s most influential art figures accused Sewell in an open letter to the Evening Standard of homophobia, misogyny and hypocrisy, among other things. But it’s not just the artists and gallerists at the sharp end of Sewell’s criticisms. As he puts it rather memorably: “Editors don’t care who the art critic is, as long as there is some blithering about important exhibitions, to which,” he pauses for a sly grin, “he may perhaps have been invited…”

From here it’s a natural step to the discussion of art criticism more generally. Obviously it’s a subject close to his heart and one in which he both despairs (“We don’t really matter, we’re pissing in the wind. And that’s it. It’s not a career I’d recommend to anybody.” and exults: “What drives me to go on is a passionate interest in the arts and a deep regret that so few people actually know how to enjoy them. And that applies to curators and directors of museums and so on.” It is this fearless / wilfully provocative approach to the powers that be that is Sewell’s most noticeable quality. But, for me, it is the clear and open passion for his subject, allied to an unsurpassed wealth of knowledge gathered over decades of looking, that earn him the right to pass such judgements, seemingly from up on high. He simply knows more than other critics, and cares less about his own personal reputation.

Right at the end of the interview, I ask him for his advice for a young art critic, and he couldn’t be more generous, or more inspiring. “My advice to any young critic would be to trust your own sensibilities,” he says, leaning forward, his eyes twinkling with contagious energy. “The more experience you have, the more complicated your life gets, the more you know and the more you feel – and the feeling is absolutely vital. You should not allow yourself to be influenced by what other people say and think. The clarity and the simplicity of your response to anything is to be trusted in the first place. Don’t embroider it with borrowed knowledge. Express an opinion that perfectly reflects how you feel about something. Everything else,” he says, “will come.”

Richard Harrison – Nothing Wasted is at JAMB, 107a Pimlico Road, London SW1W 8PH from 13th to 23rd October 2011, open daily 10am – 6pm.